Michael Campbell Plans Return to Tour Action

1 Oct

Article reprinted courtesy of Andalucía/España Golf

Like many golf stars of his generation, Michael Campbell followed an arduous path to eventual global success. Born in Hawera (Taranaki) on New Zealand’s North Island in February 1969, he left school early, worked a full-time job while fine-tuning his game among the elite of New Zealand amateur golf, made his first inroads into the professional ranks on the Australasian Tour (during an era when Greg Norman was at his peak), then headed to Europe where, competing against a golden era of international champions, he worked his way up to become one of the Tour’s leading players.

In 2005, he reached the pinnacle of the sport. His year began slowly, with missed cuts in his first five starts, before he qualified for the U.S. Open through sectional qualifying (requiring a two-metre putt on the last hole to secure a place in the third major of the year).

After three rounds at Pinehurst, Campbell was four strokes behind the leader and defending champion, Retief Goosen. As the latter floundered on the final day, Campbell played solidly to close with a one-under 69 and beat second-placed Tiger Woods by two shots. He was just the second New Zealander, after Bob Charles (1963 British Open), to win a major.

Later that season, the New Zealander finished tied for fifth in the British Open Championship, was joint sixth in the U.S. PGA Championship, won the World Match Play Championship at Wentworth, and finished second on the European Tour order of merit. Those were to be his last victories (at least to date), however, and in 2015 he decided to retire from professional touring golf.

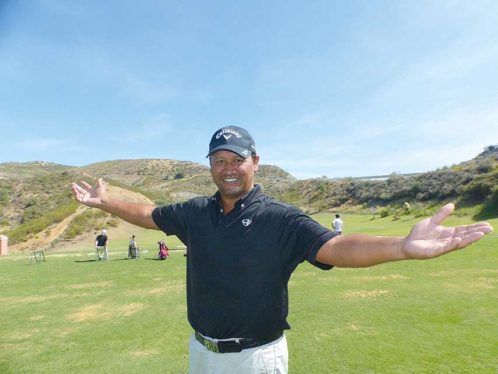

In the meantime, he and his family had moved to the Costa del Sol and bought a home alongside the Flamingos course in Villa Padierna resort, where he set up an eponymous golfing academy – later adding a second one at Calanova in Mijas-Costa. In this exclusive interview with Peter Leonard for Andalucía Golf/España Golf, at his picturesque, state-of-the-art academy in the hills above Marbella, 48-year-old Campbell talks about his rise to the top, his new life in Spain and his plans to return to European Tour competition next year as he prepares for the senior tours in 2019.

This year is Andalucía Golf/España Golf’s 30th anniversary. What were you doing in 1987?

I actually had a full-time job, working at Telecom in Wellington after Ieaving school early at 16. I sat down with my parents and had a plan: to qualify with some kind of vocation, or apprenticeship. It took four years, and I had a full-time job from 9 to 5, but my passion, my desire, was always to play golf as a profession. So back in ’87 I was pretty much working my butt off, trying to save some money, buy a car, just to please my parents really. I’m a qualified telephone technician, so if your phone breaks down I can come and fix it, although not mobiles (laughs).

When I was 16 my handicap was six. I was a late developer. That’s one thing I say to my students now: do not compare yourself with anyone else. So I was okay as a player but when I was 18, 19 that’s when things kicked off for me. I got stronger, taller, and that’s when I really decided to focus on playing golf for a living. As I said, I was a late developer in a golfing sense, especially compared to these days. It’s completely changed now, although obviously technology and coaching knowledge has changed over the last 30 years, so you can’t really compare yourself to 30 years ago. I wish I’d had the technology 30 years ago that these kids have now. I think I would be slightly better than I was when I was playing.

Were you able to travel much as an amateur, to events such as the British and US Amateurs?

No, I couldn’t afford to go. The opportunities that these kids have now, the funding from the local golf federations in their country, the sponsorship deals they have, it’s fantastic. It gives them opportunities, it means they can probably develop quicker as players because they have the exposure of playing internationally, on different grasses, in different atmospheres and with different conditions.

That’s why I think you can see such big improvements, although it’s a normal evolution as well. If you look at all sports across the board, rugby players, football players are bigger and stronger, and faster. The same with these young golfers. They’re fitter and stronger; they’re hitting the ball further, with the help of a combination of technologies. So it’s just one of the things that has developed over the years, especially the last 30 years.

In 1992, the same year you won the Australian amateur championship, you were able to travel to Vancouver (Canada) for the Eisenhower Cup and helped the New Zealand team win the world amateur golf championship…

That’s when it really kicked off for me, winning the Eisenhower Trophy, coming second in the individual. I was pretty high up there and I thought okay, this is the pinnacle of amateur golf, I can’t get any further than that, so I decided to turn professional a year later.

How did that go?

My first professional event in Melbourne I came seventh, my second one I was second, and I won my fourth one. So I tasted success very quickly in a short space of time. This was when Greg Norman was playing in these events, so it was pretty cool to beat Greg, the number one player in the world then, back in ’93. I had a great kick-start to my career but in golf, like any sport really, you can come crashing down very quickly.

You won three European Challenge Tour events in 1994, finished fifth on the main tour’s order of merit in 1995, then you were outside the top-100 in 1996 and 1997. What happened?

The first year as a pro I was only exposed to the best Australasian players and, when I came over to Europe in ’94, Faldo and Langer were playing, Seve was then still playing, Sandy Lyle, Ian Woosnam, and the list goes on and on. So I was very exposed to that and I thought, hang on, I need to work harder. I think I got too comfortable in Australia, and that’s why I had to really increase my work ethic, which I did, fitness-wise, everything, so it was a good wake-up call. I think when you come across hurdles in your life you’ve got to learn from your mistakes, and adjust your mental state and also your physical state. I needed to work harder basically.

Over the following few years you rose back up the rankings, including fourth on the 2000 order of merit and eighth in 2002, while winning six Tour events. Then came 2005 and, after a slow start, your U.S. Open triumph. What changed – if anything?

It’s just like anything – it’s confidence. Confidence breeds confidence. I was on a high, a run, and then I won the Match Play after that. After the U.S. Open I played some nice golf but after 2005 I got too busy off the golf course. That’s one thing that I would change if I had a time machine.

You get inundated with all these requests and I couldn’t say no to most of them so I was saying yes to everyone. I cut my tournament play from 28 to 15; I practised less. I was raising funds for charities, being invited here and there around the world. I was trying to make the world a better place by doing that but my golf suffered. But it was still worth it, because I take full responsibility for my actions. I decided to take that path, but unfortunately my golf suffered.

You and your family subsequently moved from England to Australia, back to Europe, to Switzerland, and then you settled on the Costa del Sol. How did the academy come about?

When we first moved here back in 2012 I saw this great opportunity for a golf academy. So I approached the Villa Padierna owner, Don Ricardo (Arranz), and he said it was a great way for me to share my knowledge and experiences with these kids. It’s been great that I’m back involved in the game that’s given me so much.

That’s one thing that Jack Nicklaus said to me when I had a conversation with him after winning the U.S. Open. He said that as a major winner you are responsible to help grow the game, so that’s why I’ve been here for three years now. It’s getting busier and busier and it’s been fun developing my own brand down here – also at Calanova. I’ve got a great bunch of staff. Steve Palmer (academy director) and the rest of the guys are fantastic; they’ve really been working very hard. My satisfaction now – each time I go away from coaching, today for example – is just knowing that I’ve helped someone in some sort of way to improve their game.

I call them “Michael’s Monsters”. I’m creating monsters, like Frankenstein (laughs).

What is you general coaching philosophy?

It’s holistic, everything about the game, not just swinging a golf club right or putting straight or hitting bunker shots well. It’s about the mental game; it’s the whole package. We work on nutrition, what you eat before you play, after you play. We work on a fitness programme for them. I have lunch with them sometimes. We talk about life on tour, what it’s like out there, all the positives and negatives and what you can learn from it. There’s so much that these kids can learn, because they’re new, they’ve just turned pro or some are about to turn pro soon, and I think for me to talk to them about life on tour gives them a great head start, learning about what to expect out there.

Presumably your advice varies from player to player… when they should turn pro, or if they should wait a little longer?

Most of the kids I’ve actually come across are ready to go, in their early twenties. There’s one young pro on the Spanish tour, I said no, you shouldn’t go to the qualifying school at the end of the year because you’re not ready. He’s still got things to work on.

Earlier this year, you launched an elite student coaching and education programme in conjunction with The American College in Marbella, the Michael Campbell Golf College course, which has been designed for golfers seeking to become professional players at the same time as working towards a university degree. Is that now up and running?

We’ve got five students here now. It’s a great opportunity to get a degree in something as well as do what they love. Their passion is to play golf, so they can combine both. There’s a four-year plan: you can spend two years here and two years in America or vice versa. One student is from America – he’s currently spending time here – and the others are European.

This must be a considerably different situation compared to when you started to play golf?

When I grew up back in the eighties, it was very unusual for a kid of Maori descent to play golf, because everyone played rugby or rugby league. So I kind of broke the mould a little bit. And the funny thing about it is that when I was at school I never told my friends I played golf because it was portrayed as an old man’s, a rich man’s sport.

Even in New Zealand with it’s golfing history?

Oh yeah, big time. It had the stigma of that. So I decided not to tell anyone, and just play weekends or after school. Because I knew if I told my friends I’d be ousted from my circle of friends. And now they all play golf!

Are there similarities from that period in New Zealand with the current situation in Spain?

In Spain it’s also very hard because they’re mad about their football over here. Golf is slowly creeping up there but it will never be as high in popularity as football obviously. Hopefully we can change the attitude of a lot of the kids out here, because things have changed.

The generations now, to a certain extent, want instant gratification. Golf courses are being built with six holes, 12 holes, or nine par-threes, so it’s evolved over time and social media has changed things. With the internet it’s changed everything because back in the eighties we had nothing. All we had to do was go outside and play; we didn’t have computers or mobile phones.

And back in New Zealand?

I think New Zealand has punched well above its weight when it comes to golf. With Bob Charles, Lydia Ko and myself winning majors… so it’s creeping up there. I’d love to be involved with the development of the game in New Zealand but unfortunately it’s just too hard – it’s too far away.

What about your own sons? Any possibility they will follow you into a golf career?

There’s an interesting story behind that. After I won the U.S. Open, Callaway wanted to release a new set of golf clubs for kids, and I said, well, my son Thomas, he was eight then, plays golf. And they said perfect, perfect scenario. He had played golf ever since he was two years old, for six years, and I said to him, “Tomorrow we’re going to play golf,” and he was pretty excited, “but there’s going to be a few people watching.” So we turned up at the golf course and there was probably 20 people there shooting a commercial, cameramen, copywriting staff, newspapers, magazines, soundmen, producers, and he completely freaked out. He stopped playing, didn’t touch a golf club until about two years ago. He’s 19 years old now, and I played with him last week. He’s so good, it’s frightening.

And your other son?

He’s 16 and more arty. They’re both very sporty but he’s more into acting and drawing and that kind of thing. They’re different characters completely.

You’ve dabbled in broadcasting and golf course design, and have previously said you lost interest in playing competitively. But perhaps a few events on the senior tours?

Funnily enough, I’ve been practising a little bit now and I’ve still got an exemption on the European Tour so I’ll probably play a few events next year then break onto the U.S. Champions tour in 2019. I’ll definitely play the European Seniors Tour as well.

I’ll just use the events I play on the European regular tour to warm up. No expectations, just go out there and play. I haven’t seen the boys for a long time. I’m sure there will be a lot of new faces out there. I’m looking forward to it.

Your competitive juices have returned then?

I think what’s happened to me is that over the last year or so I’ve been watching golf a bit more. I didn’t watch golf at all for three years, when I retired. And the last 12 months I’ve been watching golf because I kind of had to, because of my commentary (Fox Sports and Blue Sky Sports) – I had to do some homework, some research. So that started it really.

Also, what I’ve observed is that when I used to play I just did it. “How do you play a bunker shot?” “I just do it.” But teaching these kids now I have to put feelings into words, into instructions, and it’s actually made it more powerful for me to know what I’m doing rather than just feel it. It’s a combination of feel and technique. I play probably four times a year and that’s it. And people ask me how do I chip, and at first I’m going, I don’t know (laughs), but then I have to kind of check myself and think about it and translate it into words.

So you were basically self-taught?

No, my coach always told me what to do. I listened to him but it was more of a feel thing rather than following his words and advice. So that’s translated to me now coaching the kids – and grown-ups. They really enjoy that whole aspect of being coached by someone who can play as well. You don’t see that very often. You don’t see it with David Leadbetter or Butch Harmon because they can’t really play golf at the top level, although they can teach wonderfully, obviously. Pete Cowan, the same thing, amazing coach but can’t play. Not that I’m saying I’m like them when it comes to coaching; I’m nowhere near their level of coaching, absolutely not.

I remember I used to ask a lot of questions when I was on tour: how do you putt, how do you chip? And a lot of players don’t know how they do it. I’d ask the question and they would think, I just do this, and they’re actually not doing it at all – they really don’t know.

You played against Tiger Woods at the peak of his career – and beat him. If he never plays again (or even if he does), what do you believe will be his main legacy in the sport?

You played against Tiger Woods at the peak of his career – and beat him. If he never plays again (or even if he does), what do you believe will be his main legacy in the sport?

Obviously it’s been tarnished with his nocturnal activities, but I look at the big picture. He changed the course of the game. When he came out in ’97 and won the U.S. Masters, it changed the level of golf. Golf is played how it is today because of him. He evolutionised the whole game. He lifted the bar, and what he did was incredible, 14 majors. I was pleased to beat him when he was pretty much the best player in the world by far. He’d just won Augusta three months before, he’d won 10 majors, he was after his 11th major, and I stopped him, so I was quite proud of that.

The world ranking top-10 includes seven twentysomethings (Spieth, Thomas, Rahm, McIlroy, Day, Fowler, Matsuyama). Has it become a young people’s game or is this just a passing cycle?

I think that’s the way it’s going to be for a long time. Once again, the game has evolved. The general consensus among all the top players in the world used to be that you don’t really mature as a player until you’re 35. Well that’s changed completely. You’re looking at mid-twenties, early-twenties now. They are winning on tour at 21, 22. Incredible, but it’s just the way that golf has evolved. I’ve said many times before that it’s just a fact of life: these kids are getting better and better. Technology’s helped a lot – that’s definitely one thing that’s changed – and coaching, a combination of a lot of things. TrackMan’s changed it: all these gizmos, all these gadgets.

What in your opinion are the key attractive aspects of playing golf in Andalucía, those that lure people to play here?

The first thing is accessibility to golf courses. Second is the weather. And I think it’s the Spanish culture that people like too. They like to play early in the morning, have a late lunch, at two o’clock, and then maybe play another round, and then have a late dinner. So it’s conducive to playing lots of golf, at many different courses. There are more than 100 golf courses in Andalucía – that’s a big selection to choose from. So it’s a combination of many things that attracts people here, but mostly it’s the weather, because it’s pretty much like this (mid-September) all the time.

Recent Comments